"Stick" by Valerie Senyk

Reviewed by Heather Cardin

This is a raw book of pain. Aside from the geography of “Undiscovered,” which queries the disappearance of exploration, assigning it an unmerciful death via rhetorical questions, and concluding, “I’m up for grabs…/so climb me,” the book conveys a sense of loss. The rhetorical question it answers for real, the most important one, is embedded in “being human”: “What songs can my blood and bones invent/to give voice to this grace and pain?”

The emotive journey of the poems cries out from this paradoxical ‘grace’ and ‘pain’. The subject must reinvent her value, in the face of “who” she is becoming: the deliberate pun of “un/adulterated.” She’s down (in weight, in heart) but not broken: she knows that something else, perhaps someone else, could fill her up: that someone else is a lost self, hungry, from the title poem: “put her on a stick at the crossroads/with a dangling carrot…/keep her salivating,/as though a full belly/lies just a wish away.” Yet, she cannot eat. The ironic title of “in/vulnerable” betrays her: she is so deeply vulnerable that she must remind herself, “I have a future.” Recovery counts on this. The geographic theme is also found in “mapping” as she shares her journey over the land that is her ‘reefs’, ‘Badlands’, ‘dry bowl’, ‘islands’, ‘sand-pies’ and ‘splayed fiords’, to the harsh reality of her mouth, which is, unsurprisingly, a ‘secret gorge’: “My mouth is like my cunt.” This is a scream, from a stick.

And yet, despite all this power, and its “body of literature”, the most telling poem, for this reader, is “like my mother’s”, because, perhaps, all women become their mothers. It is a poem in need of italics, the emphasis of “I stand more still now” and “my mother’s frame.” Indeed, the very brevity of the chapbook reveals the universality of woman-language: ‘toppled’ and ‘denuded’, yet, we are ‘drummed’ up “from underground/bones rich as old ivory.” There is a hesitant resurrection reminiscent of old tales of women, cornered and groaning, and yet, still capable of “the crumbs of love.” She speaks of possibility, in rediscovering ‘who” she is, this stick. She is on a quest, as is clear from her opening poem, after a “harrowing experience”: “seeks attar;/chooses the path/of the wire; to hum//an atonal breath/buffeted by/peculiar winds of change.” In this, she is every woman, and herself: we are buffeted and tossed about, all with the necessity of change, hard come by. As she notes, her friend’s question, the only other italicized query: “do you not bring your past/into the present/as part of you?” Of course. That’s why it hurts.

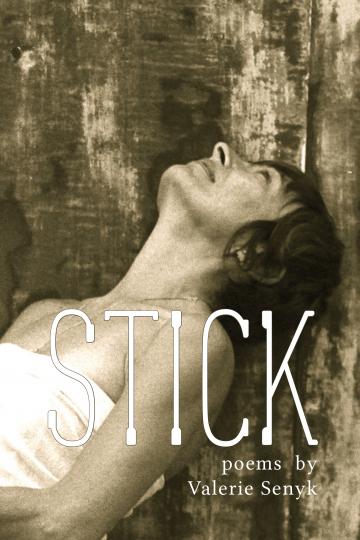

This is a bloody, naked collision, as the language of “in/vulnerable’ indicates openly, as the photographs throughout the collection show us. Occasionally, a glimpse of betrayal stirs: “now I’d sooner be read/in public/than see your writing on the wall’, an elegant allusion to the man who has frozen her, taken her “in swampy reeds off the highway.” This is a booklet about being fucked, literally, and asking, “Look at me; what does this transformed body mean?” That’s its own answer, as in any rhetoric: it’s the “awful responsibility of being human.”

Don’t read this book if you’re hurting. Or maybe, do, and feel empathy with this woman, this stick, who fights her way through language to “…a man with blue eyes”, blueberries, crushed and overripe, and “God’s name on her tongue.” Has she also become larger? She asks, “Have my responsibilities diminished to,/this spaciousness an unlooked-for freedom?”

Perhaps she’s found “a melody and a drum.” As with all stories, this one’s still growing. The brevity of the booklet leaves the reader wondering, a rumination on betrayal, hopelessness, and rising above ground towards some inchoate light.